The NCAA is one of the most powerful college sports leagues in the world. According to data from the U.S. Department of Education that was compiled by USA Today, the 231 NCAA Division I schools with data available generated $9.15B in revenue during fiscal 2015. NCAA coaches make millions, but until now NCAA college athletes have not be allowed to be paid.

NCAA regulations strictly prohibit remuneration for any activity by any student-athletes, including endorsements, appearances and advertisements, beyond scholarships, to retain their amateur status.

But the no-pay rule has become increasingly unpopular. Now lawmakers in a handful of states want to allow college athletes to be paid, if not directly in a salary, then by allowing compensation for the use of their image, likeness or name.

This could soon become a reality in the future as last Tuesday the NCAA announced it was starting a “process to enhance name, image and likeness opportunities.”

“We must embrace change to provide the best possible experience for college athletes,” said Michael V. Drake, NCAA Board of Governors’ chair and president of the Ohio State University. “Additional flexibility in this area can and must continue to support college sports as part of higher education.”

The NCAA’s top governing board voted unanimously to permit students that participate in athletics the opportunity to benefit from the use of their name, image, and likeness.

So what’s next?

From the vote, each of the NCAA’s three divisions is meant to consider updates to bylaws and policies. The vote included a variety of guidelines when it comes to modernization, which the NCAA says is “meant to maintain the sanctity of college athletics.”

The guidelines include the assurance that athletes aren’t treated differently than non-athlete students, education remains a priority, that there are transparent rules, and enhanced principles of diversity, inclusion and gender equity, among others. The initial board vote doesn’t change anything, but it does push the rules decisions to each of the three divisions, asking them to create new rules immediately, but no later than January 2021.

This action came from a workgroup of presidents, commissioners, athletic directors, administrators, and student-athletes, which will continue to gather feedback through April “on how best to respond to the state and federal legislative environment.”

Clearly there is still a way to go before college athletes start getting compensated, but at least we are on the right track.

“As a national governing body, the NCAA is uniquely positioned to modify its rules to ensure fairness and a level playing field for student-athletes,” NCAA President Mark Emmert said. “The board’s action today creates a path to enhance opportunities for student-athletes while ensuring they compete against students and not professionals.”

The NCAA’s announcement comes less than a month after California passed a law requiring the schools in its state to allow college athletes to profit from their name, image, and likeness. That law is set to take effect in 2023.

The NCAA has since faced growing pressure from legislators across the country. The association had threatened to bar California from its competitors and said it believed the bill was unconstitutional.

In a Q&A posted on its website, the NCAA wrote that “the action taken by California likely is unconstitutional, and the actions proposed by other states make clear the harmful impact of disparate sets of state laws. The NCAA is closely monitoring the approaches taken by state governments and the U.S. Congress and is considering all potential next steps.”

Public opinion: 52% believe NCAA athletes should get paid

A poll conducted in March of a thousand registered voters nationwide by ScottRasmussen.com and HarrisX polling firms found that more than half (52%) of those surveyed thought that college athletes who play for major revenue-generating sports programs should be paid.

The survey, which has a margin of error of 3% points, found 32% thought student-athletes should not be paid and 16% were not sure. When asked whether the athletes should be compensated if a school sells merchandise with a player’s name or picture on it, 64% said they should.

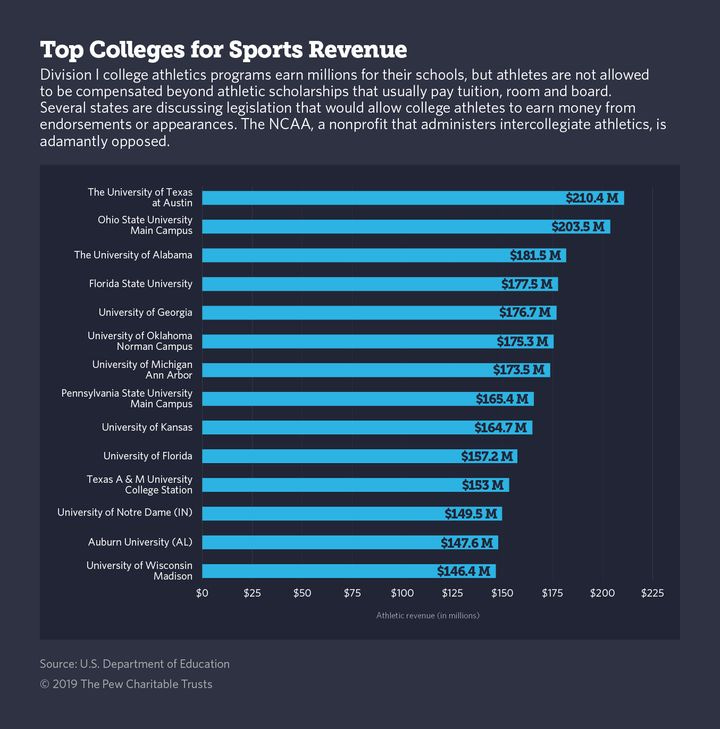

So what are the top US colleges in terms of sports revenue?

According to the US Department of Education, the university of Texas ranked first in terms of sports revenue with a total of $210M. Ohio State University and the university of Alabama ranked 2nd and 3rd, with $203M and $181.5M in sports revenue, respectively. This is part of the national debate: If US college are making so much money, why can’t US college athletes get compensated as well?

Who are the highest paid NCAA college head coaches?

Who are the highest paid NCAA college head coaches?

NCAA coaches are also well compensated. In fact, ten coaches across major-college football will make more than $6M during the 2019-2020 season, according to data compiled by USA TODAY Sports. The average total pay of the 122 FBS coaches’ salaries obtained by the newspaper is $2.67M, up 9% compared to last season and the largest increase that it has tracked in the last four years.

In total, USA TODAY Sports obtained the salaries of 122 of the 130 FBS coaches.

The Highest Paid Coaches

- Dabo Swinney – $9,315,6001

- Nick Saban – $8,857,000

- Jim Harbaugh – $7,504,000

- Jimbo Fisher – $7,500,000

- Kirby Smart – $6,871,600

- Gus Malzahn – $6,827,589

- Tom Herman – $6,750,000

- Jeff Brohm – $6,600,000

- Lincoln Riley – $6,384,462

- Dan Mullen – $6,070,000

So how many NCAA athletes could be compensated in the future? 500,000 athletes could benefit from it.

A total of 500,000 young men and women across 1,100 NCAA member schools could be impacted here and start getting compensated as a college athletes.

Now big brands such as Nike, Adidas, Under Armour will continue to be selective when it comes to endorsing the next super star.

“In the marketing offices of Nike and Under Armour, they’re looking at individual athletes and programs who have the most promising records and who look like a good bet for the future,” O’Keefe said.

The experts based their numbers on deals that college athletes have received after they recently turned pro, adding that a definite range doesn’t exist yet because the market for college athlete endorsements hasn’t been created. One example is when Golfer Justin Suh left the University of Southern California this past summer and turned pro and soon after signed a three-year endorsement deal with Titleist reportedly valued between $500,000 and $750,000.

One injury away from never playing again

Local sponsorship dollars that experts are predicting, though not in the millions, are still likely to be significant for students because “they’re always one injury away from never being able to play again,” O’Keefe said. The sponsorships are “a little bit of money they can sock away for a rainy day,” he added.

Henry Hebda, a junior football player at Indiana’s Valparaiso University, said extra money from sponsorships would help student-athletes who are upperclassmen pay rent and utilities if they move to off-campus housing. The money could also go toward nutrition supplements for weight training and body conditioning, he noted.

“It would definitely help some of us get extra food that we need to gain weight,” said Hebda, 20, who plays cornerback. “People spend a lot of money on that and on buying post-workout drinks.”

Moriyah Hamell, a freshman basketball player at Niagara University in Lewiston, New York, said she doesn’t have a job while attending school. She said she’s living solely off a refund check from her student loans. The opportunity to profit from an endorsement or sponsorship would help all college athletes feel more financially stable, she said.

“Having money from the outside means you can buy whatever you want or need,” said Hamell, 18. “And me, not coming from a financially wealthy family, I would use that to buy a winter coat or boots.”

NCAA set to continue to lobby hard in DC

The NCAA spent $400,000 on lobbying politicians in the two-year election cycle of 2016-17, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonpartisan group that tracks political fundraising and spending. By contrast, the NFL spent $1.6 million, while the PGA spent only $120,000.

Lobbying disclosure records for the U.S. Senate show the NCAA lobbied on issues relating to amateur status of college players and hired Washington lobbying firms to the tune of $640,000 in 2018.

With that in mind, we believe that the NCAA is set to continue to lobby in DC to protect its own interest.

Bottom line: There is still a long way to go before seeing NCAA college athletes being legally allowed to be paid. But when that happens, we are likely to see a growing number of college athletes endorse or invest in sports tech startups. Now not all college athletes will become millionaires overnight, but with all the money generated by NCAA colleges, NCAA coaches, it only seems fair that college athletes get a piece of the profit. The only question is: How long will it take before it happens? It is still everybody’s guess at this point, but we are moving in the right direction.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.